Vaccines offer hope for brighter future

As strange as it may seem given that cases of and hospitalizations with the novel coronavirus are worse than they have ever been in this area, the world has recently gotten its clearest glimpse of the light at the end of the tunnel that is this pandemic.

That is because three COVID-19 vaccines, developed by Pfizer and BioNTech, Moderna and the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca, have been announced in the last two weeks. Data so far shows two are over 90 percent effective and another is more than 70 percent effective.

One or all of those are on track to possibly be available on a limited basis by the end of the year.

The Pfizer and BioNTech vaccine has undergone its last efficacy analysis in the third and final phase of clinical trials, and it has a 95 percent efficacy rate.

In this study, there were about 38,000 participants, half of whom got the vaccine and half of whom received a placebo.

Of those people, 170 people contracted the virus, and only eight of them were in the vaccine group. Ten of those cases were severe, and only one of those was in the vaccine group.

With that success, Pfizer and BioNTech, which did not take government funding for vaccine development, announced Friday they are submitting an Emergency Use Authorization request for the vaccine to the Food and Drug Administration.

Meanwhile, Moderna’s vaccine has shown a vaccine efficacy of 94.5 percent in a preliminary analysis of its Phase 3 study.

Over 30,000 people have participated in Moderna’s clinical trial. So far, there have been 95 cases of COVID-19, only five of which were in the group who received the vaccine.

None of the 11 severe cases were in the vaccine group.

Moderna’s vaccine is not as far along as its Pfizer and BioNTech counterpart, but the rapid spread of the virus should allow it to catch up faster because the study will not end until there have been 151 confirmed cases and a median follow-up of more than two months.

Moderna did utilize government funding in its vaccine development and has been working with the National Institutes of Health.

Oxford and AstraZeneca announced Monday that their vaccine has shown an efficacy of 70.4 percent in two large-scale trials, but that number goes up to 90 percent if a lower dose followed by a second, full dose is used.

That analysis is based on 131 symptomatic coronavirus cases among participants in the study at least two weeks after they received their shot. None of those individuals required hospitalization.

Developed in Europe, the university and company have said they plan to seek authorization for the vaccine in countries there, though the timeline in America is not clear.

This vaccine has the benefits of being cheaper to produce at $3 to $4 a shot and easier to store because it does not require extremely cold temperatures.

The next steps are for the FDA to determine whether to authorize the vaccines for emergency use given the public health crisis the pandemic poses.

To get that approval, a coronavirus vaccine must show it is “effective to prevent, diagnose or treat such serious or life-threatening disease or condition” caused by COVID-19, its benefits outweigh the “known and potential” risks of the vaccine and that there is no “adequate, approved and available alternative to the product for diagnosing, preventing or treating” the virus, per the FDA.

At that point, an approved vaccine could begin being distributed.

But the companies that created the vaccine would still follow the rest of the normal regulatory process, the next step of which is an in-depth Biologics License Application followed by an inspection of the manufacturing facility, presentation of findings to the appropriate FDA committee and usability testing of product labeling, according to the FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Once the FDA authorizes a vaccine, the Illinois Department of Public Health has a plan to allocate doses to counties based on population.

Monroe County Health Department Administrator John Wagner said he does not yet know how many doses Monroe County will receive because Illinois does not know many it will get.

The IDPH reports the Pfizer and BioNTech vaccine, which must be stored at “ultra-cold” temperatures of -60 to -80 degrees Celsius, will likely be shipped in 1,000 dose increments.

That would be enough for 500 people to get fully vaccinated, as both vaccines require two shots a few weeks apart.

Wagner said it is unclear, however, if the state will instruct county health departments to fully vaccinate 500 people or give the first shot to 1,000 people in anticipation of more doses.

“We have storage for the not ultra-cold vaccine,” Wagner said, referring to the Moderna vaccine, which must be shipped or stored long-term at -20 Celsius but can remain stable at refrigerator temperatures for up to 30 days. “For the ultra-cold vaccine we do not have storage, but with the volume that we’d get, we’ll be able to get rid of it in the time before it runs out.”

The first doses of the vaccine will be prioritized nationwide. The IDPH’s top priorities are to vaccinate members of the critical workforce like health care workers and first responders, staff and residents of long-term care facilities and critical workforce members who work in essential jobs.

Wagner said 1,000 doses would be plenty to vaccinate at least the first responders here.

Estimates vary on how many doses will be available across the country, though most experts agree a vaccine will be available to the general public beginning around April or even March.

Regardless of the timing, when Monroe County distributes a COVID-19 vaccine, it will do so at the Monroe County Fairgrounds using a drive-thru clinic with weather protections for nurses administering the vaccine.

If it gets enough vaccines, Wagner said his office could vaccinate the county’s entire population in under a month.

“We’re organized right now, and our plan is, if we get enough volume, we will be running it around the clock — 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” he said.

To make that happen, Wagner said he will need an as yet undetermined number of paid and unpaid volunteer nurses.

The CDC reports that 70 percent of the population must be vaccinated in order to achieve herd immunity, but as the state and country works toward that number Wagner said it will remain important to continue practicing precautions like social distancing, washing hands frequently and wearing a face covering.

“Once everybody who wants it gets vaccinated, it solves a whole lot,” Wagner said. “The problem is until we get everybody who wants it vaccinated, there’s still going to be spread into people who you want to get protected. So, you don’t want people getting sick who are just waiting to get the vaccine.”

Wagner further noted there are people who cannot get the vaccine due to health reasons and that some will decide not to get it, so his office will continue contact tracing and trying to contain the spread of the virus for the foreseeable future – even with a vaccine.

Additionally, the CDC reports that, even after getting vaccinated, individuals should continue following the appropriate preventative measures because experts will need to study how the vaccine works in real-life conditions before recommending stopping those efforts.

As daunting a logistical challenge as storing and distributing the vaccine will be, perhaps the most challenging part of achieving herd immunity through vaccination may be convincing people to get the shots.

According to the latest data from Pew Research Center, 51 percent of U.S. adults report they would definitely or probably get a COVID-19 vaccine, while 49 percent said they definitely or probably would not.

That data, however, is from September, well before the latest promising results were announced.

To combat fears of vaccination, it is important to note that two of these coronavirus vaccines work differently than many others because they will be the first that use messenger RNA technology.

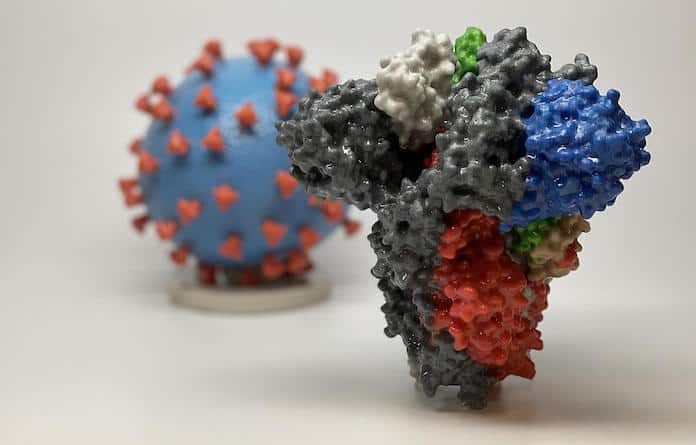

Normally, a vaccine uses a weak or dead version of a virus. With this technology, the COVID-19 vaccines use a small portion of the virus’s genetic code to tell cells to build the signature spike protein on the surface of the virus, thereby teaching the immune system to recognize and destroy the real virus.

“It’s a little bit of a new technology with how it’s working and how it’s triggering your response,” Wagner explained. “But…once something makes it to the Phase 3 trial, it is deemed safe at that time.”

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, however, uses a weakened version of a chimpanzee adenovirus as a delivery vehicle to ferry coronavirus genes into human cells and train the body to fight future attacks from the actual coronavirus.

People may also be concerned because the coronavirus vaccine, if authorized this year, will have been created in months. The previous record for vaccine development was for mumps, which took four years.

Despite that potentially alarming speed, experts have assured the public the vaccine will be safe, in large part because it has been created using many of the same technologies and practices used to develop other vaccines and because the virus’ genetic sequence was shared worldwide.

The CDC points out the United States has a longstanding vaccine safety system that ensures new vaccines are as safe as possible, crediting the clinical trials and post-licensure safety studies as being key to that process.

That does not mean a vaccine will be 100 percent safe, but its benefits will outweigh the risks.

While there may be long-term side effects of getting the vaccine, Wagner said the same is true of getting the virus.

“We don’t know what happens 20 years down the road with somebody who gets COVID,” Wagner said. “There’s scientific research that tells you we’re pretty sure nothing is going to happen, and that’s what they’ve done with the vaccine.

“You’re more likely to have adverse effects in the long run from getting the disease itself than you are from getting the vaccine.”