Tracking graduated income tax history

With early voting underway and Election Day less than a month away, one of the main concerns with the graduated income tax amendment on Illinois’ ballot is that it would give lawmakers a blank check to raise taxes.

State Sen. Paul Schimpf (R-Waterloo) made that argument when he voted against the measure last year.

“Changing our taxing structure, without providing a means to limit spending or make it more difficult to raise taxes in the future, solves nothing,” Schimpf said. “In fact, this plan will most likely only lead to more tax increases and higher spending in the future.”

To help provide context to this possibility, the Republic-Times examined the changes in graduated income tax rates and brackets among all 32 states that used that system from 2010-2020.

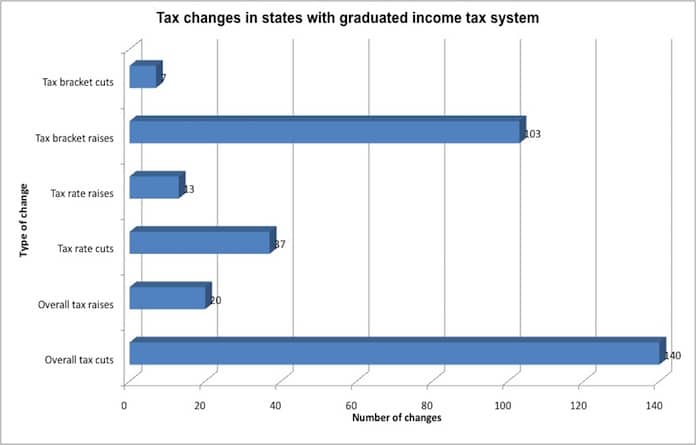

In that time, states actually lowered taxes more times than they raised them.

This analysis does not guarantee or predict what Illinois would do using this system because every state is different, but it does provide some food for thought.

Before delving into the numbers, it is important to note the text of the constitutional amendment on the ballot does not set the rates for the proposed tax system. It only removes the portion of the Illinois Constitution requiring a flat tax and replaces it with language for a graduated income tax.

“The proposed amendment grants the state authority to impose higher income tax rates on higher income levels, which is how the federal government and a majority of other states do it. The amendment would remove the portion of the Revenue Article of the Illinois Constitution that is sometimes referred to as the ‘flat tax’ that requires all income be at the same rate,” the proposed amendment on the ballot reads. “The amendment does not itself change tax rates. It gives the state the ability to impose higher tax rates on those with higher income levels and lower income tax rates on those with middle or lower income levels.”

The General Assembly voted last year on what the initial tax rates would be if this amendment is ratified by 60 percent of those voting on the amendment or a majority of those voting in the election approve it.

If the amendment passes, those who file a tax return as single pay 4.75 percent on taxable income up to the first $10,000; 4.9 percent on income between $10,001 and $100,000; 4.95 percent on income between $100,001 and $250,000; 7.75 percent on income between $250,001 and $350,000; 7.85 percent on income between $350,001 and $750,000; and 7.99 percent on all income if a single filer makes over $750,000.

For joint filers, the same rates apply but they cover different ranges. The 7.75 percent rate is on income between $250,001 and $500,000; the 7.85 percent rate applies to income between $500,000 and $1 million; and joint filers making over $1 million pay 7.99 percent on all income.

It is important to note that these brackets do not apply to individuals based on total income earned unless they are in the highest bracket.

For example, a single filer who makes $150,000 would not pay 4.95 percent on all his/her earnings. He/she would pay 4.75 percent on the first $10,000, 4.9 percent on all income after that up to $100,000 and 4.95 percent on the rest of his or her earnings.

Currently, all Illinoisans pay taxes at a rate of 4.95 percent on all income under the flat tax structure.

A common concern among opponents of the measure is that the graduated income tax system would allow legislators to raise taxes more easily – such as by raising them only on certain brackets at a time to make the changes more politically palatable.

Illinois does have a history of raising its income tax. Since 2010, the state income tax has been raised from 3 percent to 5 percent in 2010. It then dropped back to 3.75 percent in 2015 before the Democrat-controlled legislature raised it to 4.95 percent in 2017.

According to Republic-Times calculations, which used data compiled by the Tax Foundation, a tax policy nonprofit think tank, states with a graduated income tax lowered at least one tax rate 37 times from 2010-2020.

Arizona, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont and Wisconsin all lowered at least one tax rate in that time.

Conversely, states with a graduated income tax raised at least one rate 13 times. Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York and Wisconsin all raised at least one rate.

The most common income levels that saw tax rate changes were those making under $100,000 a year.

States decreased the tax rate on tax brackets below $100,000 for single filers 24 times. They raised rates on that same group 12 times.

For those making over $100,000 a year, states increased the tax rate five times and decreased it the same number.

States also commonly raised or lowered tax rates across the board in the preceding 11 years.

States dropped the tax rate 12 times for all brackets, while only Kansas raised it for all income levels. It did so twice.

These rate changes were not often seismic.

Iowa, for example, had tax rates in 2010 of .33, .72, 2.43, 4.5, 6.12, 6.48, 6.8, 7.9 and 8.98 percent for its various income brackets. When it lowered rates in 2019, it only did so by .03, .05, .18, .36, .49, .52, .55, .48 and .45 percent, respectively.

The same usually held true for tax rate increases – unless a new income bracket was introduced like when New Jersey added a 10.75 percent rate on those making over $5 million in 2019. The previous highest rate taxed all income above $500,000 a year at a rate of 8.97 percent.

As an example of fairly typical rate increases, Kansas’ 2016 tax rates were 2.9, 4.9 and 5.2 percent. Those were raised in 2018, but only to 3.1, 5.25 and 5.7 percent.

It is also noteworthy that 18 states — Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia — do not have income tax brackets specifically on those making six figures or more a year.

Therefore, changes in those states automatically affect those making under $100,000 a year.

In fact, the more common way states raised or lowered taxes was adjusting the income tax brackets, not the tax rates.

A Republic-Times analysis found that states with a graduated income tax raised the starting level for tax brackets 103 times between 2010 and 2020, while they lowered the starting income for brackets seven times.

Arizona, Arkansas, California, Idaho, Iowa, Georgia, Kansas, Maine, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New York, New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont and Wisconsin all upped the lower end of tax brackets, while Arkansas, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Missouri and Wisconsin dropped the starting point for an income bracket.

In the case of brackets, there is an inverse relationship between the low end of the brackets being raised and the effect on taxes.

For instance, Wisconsin residents in 2018 had income tax brackets of $0-$11,229, $11,230-$22,470, $22,471-$247,350 and $247,351 and above. The state raised those brackets to $0-$11,760, $11,761-$23,520, $23,521-$258,950 and $258,851 and up the next year.

That means a few hundred dollars or a few thousand dollars of income at each level was now taxed at the lower rate as the brackets expanded. For example, Wisconsin taxpayers in 2018 paid the state’s lowest tax rate on all income under $11,229. But the next year, they paid the lowest rate on all income below $11,760.

Among all the bracket fluctuations, the most common change was to raise brackets, and thereby lower taxes, for all income levels. That happened 66 times, with multiple states raising levels in consecutive years.

These increases were rarely too significant and could sometimes be negligible, like when Missouri raised each bracket’s income level by $1.

Only Wisconsin and Maine ever lowered the income levels for brackets, which raised taxes for everyone, and each state only did so once.

States also raised brackets on income under $100,000 a year 51 times while lowering them three times.

States raised brackets on income over $100,000 annually 19 times, and only one state, Maryland, lowered it. Maryland did so once.

Only Alabama, Louisiana, New Mexico, Virginia and West Virginia saw no changes to tax rates or brackets from 2010-2020 under their graduated income tax system.

Again, this does not mean Illinois would follow these trends if voters OK’d a graduated income tax system. The state could very well be an outlier among its peers.

This data does, however, give voters something to consider when deciding whether to ratify the proposed amendment.