Seeking the lost community of Kaskaskia

It has been home to Native American tribes, French explorers and traders and early American settlers.

It saw prosperity and wars and was mostly wiped away by flooding 150 years ago.

Researchers at Southern Illinois University Carbondale think much of the lost community of Kaskaskia can still be found, and locating it could teach us important lessons about our history.

Mark Wagner, professor in the School of Anthropology, Political Science and Sociology and director of SIUC’s Center for Archaeological Investigations, is leading an investigation of Kaskaskia’s original site in hopes of finding how much of the historic town still survives.

Evidence points to the possibility that more than half is still there beneath the ground on what is now the west side – largely the Missouri side – of the Mississippi River.

A major aspect of the research involves training tomorrow’s scientists, an important focus at SIUC. As the investigation unfolds, Wagner and Ryan Campbell, assistant scientist and associate director of the CAI, also will train Rebecca Ramey, a senior in anthropology, to use technology and good, old-fashioned map work to unlock Kaskaskia’s mysteries.

“Just because something is gone on the surface doesn’t mean it is gone in the archeological context,” Ramey said. “It’s important to remember our state’s history and preserve what we can. It could also potentially help the current residents in Kaskaskia by increasing tourism and boosting their local economy as they have been hit hard by floods.”

A key crossroads

The site of the original town was inhabited by Native Americans for thousands of years. The Kaskaskia tribe, part of the Illiniwek, first encountered European traders in the 1600s.

Trade and mutual defense against other Native tribes led the Kaskaskia to further cooperation with French traders and settlers. French missionaries and other Europeans eventually flocked to the area, along with African American settlers, increasing the town’s multicultural nature and solidifying its importance as a trade center ideally located on the Mississippi River.

In 1809, with a population of about 7,000, the town became the capital of what was then the Illinois Territory. It relinquished that title to Vandalia in 1819, not long after Illinois became a state.

A series of floods beginning in 1844 reduced and relocated the town, as its original site became an island in the river.

Another flood in 1881 destroyed the remnants of the original site, which ultimately ended up on the west side of the Mississippi River, still within Illinois’ boundaries as an enclave that can only be reached from Missouri.

A knowledge gap

Kaskaskia’s utter destruction by flood waters in 1881 and its current location on the river’s west side have likely discouraged archeological study, Wagner said. Simply reaching the site requires one to cross the river at Chester and take a ferry from Modoc to Ste. Genevieve before driving south to the site.

But Wagner said the Kaskaskia survey potentially offers to fill in important chapters in Illinois’ early founding.

“It’s far easier for researchers to work French period sites on the east side of the river, like Cahokia, Fort de Chartres and Prairie du Rocher,” Wagner said. “All these factors have meant Illinois archaeologists have shown virtually no interest in Kaskaskia, despite its status as one of the earliest French settlements in Illinois and probably our largest and earliest African American settlement.”

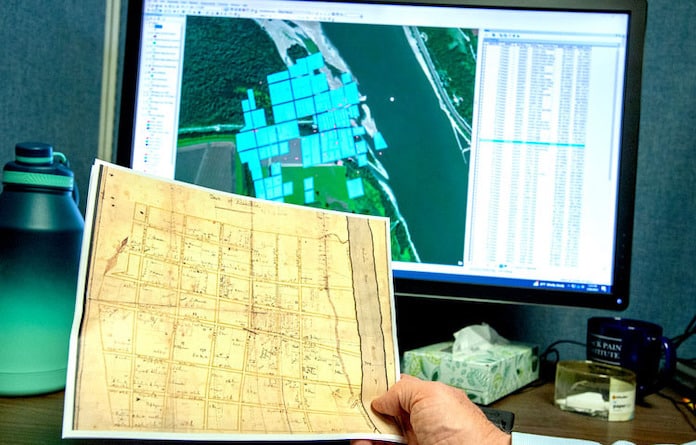

While Wagner and Campbell deal with those questions, they also will teach Ramey to use geographic information systems and archival research. Another aspect involves Ramey overlaying historic maps over modern ones, to zero in on how much of the town might potentially survive – it could be about 60 percent – as an archeological site.

“There are a number of archaeological sites representing the remains of individual French- and American-period buildings and houses,” Wagner said. “We are comparing the names of the homeowners with census data to find out who they were.”

Researchers believe at least some of those people’s homes belonged to African American families while at least one belonged to Jacques Mette, a well-known fur trader and interpreter of mixed ancestry or a “metis” man who lived in the early 1800s.

Happy accident

For Ramey, understanding what people in history did and why has become a calling.

While she initially planned to study forensic anthropology at SIUC, taking Wagner’s “Curation of Archeological Collections” class helped her discover anthropology as a many-faceted field, with numerous niches for a young scientist to pursue.

During the class, Wagner approached Ramey with the idea of surveying the lost city as well. The town’s history as the site of a fortification called out Ramey’s interest in military history as member of the U.S. Army Reserves.

“It’s interesting seeing that some of the techniques used historically by the United States military are still in effect in the modern military, or seeing how those techniques influenced the modern military,” she said. “Work directly with Dr. Wagner analyzing and cataloging artifacts from the previous year’s field school, I fell in love with the study and quickly realized that I wanted to do archeology for the rest of my life.”

Challenges ahead

As an undergraduate researcher, Ramey faces a steep but rewarding learning curve as she plunges into the project. She will scan and upload historical maps into a computer program before overlaying them on modern landscape maps to re-create the town’s location.

One important piece of evidence is a detailed map from the 1830s created by Sydney Breese, a prominent figure in the town. She will cross-reference the map with census data from the era to identify where people lived.

“The census-taker walked from house to house, handwriting down the people’s names who lived there, but only taking the male head of the household’s name,” Ramey said. “This is making it extremely difficult to identify everyone on the map.”

Ramey plans to apply for graduate school at SIUC and continue working on the project as the subject of her thesis. After that, she hopes to gain permission from the state and local landowners to conduct archeological digs on the site, with the ultimate goal of locating the remains of houses whose occupants she has identified, and possibly even artifacts.

The past is her future

Ramey hopes to become a federally contracted archeologist, applying all she learns at SIUC as a full-time career.

“The Center for Archeological Investigations has helped me immensely with obtaining this goal by giving me opportunities in research and hands-on experience that is not always offered,” she said.

The long haul

Wagner hopes to present preliminary results of the project later this year at two state historic and archaeological conferences. With the project currently funded by an SIUC Foundation grant, he also hopes to use the discoveries as proof of concept to apply for further funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities or the National Science Foundation.

“We are dealing with cultural diversity, in that Kaskaskia undoubtedly contains the earliest African American sites within Illinois, assuming we can identify them,” Wagner said.

(article courtesy of Southern Illinois University Carbondale)