Examining COVID claims

As the coronavirus pandemic has ravaged the world, it has had far-ranging and disparate effects.

One of those has been the spread of misinformation about the virus, often from sources that appear authoritative such as videos on social media or articles from media companies.

“A troubling number of purported experts are sharing false and dangerous information that runs counter to the public health and safety guidelines endorsed by (The American College of Emergency Physicians) and the nation’s leading medical and public health entities,” ACEP President William Jaquis said last week in a press release. “This kind of misinformation can not only be harmful to individuals, but it hinders our nation’s efforts to get the pandemic under control.”

At the local level, Monroe County Health Department Administrator John Wagner said doubts sown by deceptive sources can and have caused issues.

For example, people have been confused about how long they must quarantine after being in contact with someone with coronavirus, potentially exposing more people to the illness.

“It’s not always misinformation. Sometimes people may not have the most updated information,” Wagner added, using the change early in the pandemic on masks as an example.

The desire to trust and turn to dubious sources is understandable given how unprecedented this situation is for almost everyone. It can be tempting to believe something as tumultuous as a global pandemic is not as severe as purported or has sinister, man-made origins, for instance.

For this article, the Republic-Times examined five common claims about the pandemic to give readers more information to consider when deciding what they believe.

Claim: COVID-19 originated in China as a man-made weapon.

Since the early days of the pandemic, some have claimed the coronavirus came from a lab in Wuhan, China – the city where the virus began – or is otherwise a bioweapon created by the Chinese government.

For almost as long as that theory has existed, though, medical experts and United States intelligence officials have disproved it.

The Lancet, a weekly, peer-reviewed medical journal that is among the world’s oldest and most respected, published an article in February from 26 medical professionals about the origins of COVID-19. The authors cited nine studies that showed the virus was not manufactured.

“We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin,” the researchers wrote. “Scientists from multiple countries have published and analyzed genomes of the causative agent, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and they overwhelmingly conclude that this coronavirus originated in wildlife.”

A genome is the genetic material of an organism, including its DNA.

The Office of the Director of National Intelligence, which oversees America’s spy agencies, also released a statement in April about the origins of COVID-19.

“The intelligence community also concurs with the wide scientific consensus that the COVID-19 virus was not man-made or genetically modified,” the office reported.

Claim: The increase in testing has caused the United States’ recent surge in cases.

Certainly, the increase in testing has resulted in the country finding more cases of the virus, but the expansion of testing does not account for all the new cases.

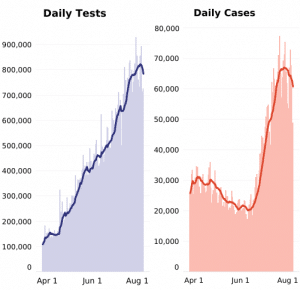

According to data from The COVID Tracking Project, a volunteer organization dedicated to collecting and publishing data about COVID-19 in the U.S., the country conducted 892,493 tests on July 31. That was an approximately 213 percent increase in tests from June 1, when America conducted 418,645 tests.

But over that same time period, the number of positive cases those tests found increased about 330 percent, from 20,415 on June 1 to 67,503 on July 31, outstripping the testing increase.

Additionally, the country’s positivity rate has risen or remained steady as testing has increased, despite experts saying it should decrease if enough testing is being done and the virus is under control.

In the midwest, south and west, the positivity rate held steady or increased even as testing rose, according to The COVID Tracking Project. In states experiencing COVID outbreaks like Missouri, Texas, Florida and California, testing remained relatively steady or slightly decreased while the positivity rate had gone up to an average of 10.8, 11.9 19.3 and 7.2 present, respectively, at the end of July.

Organizations like the Illinois Department of Public Health advise that a positivity rate should be at or below 5 percent for the virus to be considered under control and testing adequate.

At the end of July, Our World in Data, which an Oxford University program director runs, showed America’s positivity rate was around 8.8 percent at the end of July.

“Where the number of confirmed cases is high relative to the extent of testing, this suggests that there may not be enough tests being carried out to properly monitor the outbreak,” Our World in Data explains on its website. “In such countries, the true number of infections may be far higher than the number of confirmed cases.”

Claim: Hydroxychloroquine can cure coronavirus, or at least serve as an effective treatment for it.

Figures from President Donald Trump to a doctor from Yale University have promoted the benefits of a drug called hydroxychloroquine to cure or treat COVID-19.

These assertions vary from claiming the drug, which is used to treat malaria and other health problems like lupus and arthritis, will work in any stage to purporting it is effective if administered to people in the early stages of the illness.

The Food and Drug Administration did provide an Emergency Use Authorization to use the drug as treatment for hospitalized people with COVID-19 in March after it showed initial promise.

It revoked that authorization in June, however, when information – including results of a large, randomized clinical trial – “found these medicines showed no benefit for decreasing the likelihood of death or speeding recovery.”

The FDA wrote in a letter that early reports of the effectiveness of the drug were “not consistently replicated” and studies showed no difference in outcomes for people who used hydroxychloroquine versus those who got standard care.

Then, on July 1, the FDA announced that using the drug to treat the virus can cause adverse effects like “serious heart rhythm problems and other safety issues including, blood and lymph system disorders, kidney injuries and liver problems and failures.”

Additionally, the National Institute of Health reports “there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs for the treatment of COVID-19. Definitive clinical trial data are needed to identify safe and effective treatments for COVID-19.”

The NIH reports that another drug, remdesivir, has shown some effectiveness in treating those with serious symptoms from the virus, but it does not have enough data to recommend or not recommend using it in less serious cases.

Claim: COVID death counts are inflated. For example, if someone who has coronavirus dies in an automobile accident, that is counted as a death due to COVID-19.

Reporting deaths from coronavirus is surprisingly complicated.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends COVID-19 not be reported on a death certificate “if it did not cause or contribute to the death.” If the virus is an underlying cause, it should still be counted, according to the CDC.

The CDC takes data from death certificates to produce provisional death counts, which are subject to change and often incomplete.

Problems can arise on several fronts. It can take as long as 10 days to report dates of death and other information on death certificates to the CDC.

Even when taking that time, it can be “challenging, especially during emergencies” for certifiers to get data because they may not have all the information, thorough training or time, according to the CDC.

That can lead to some death certificates being incomplete or inaccurate.

“Cause-of-death information is not perfect, but it is very useful,” the CDC explains on its website. “Current estimates indicate that about 20-30 percent of death certificates have issues with completeness. This does not mean they are inaccurate.”

With all those factors, it is entirely possible some deaths are counted, at least provisionally, as being due to coronavirus when they are not.

But experts have said cases like that are extremely infrequent.

Wagner said deaths attributed to COVID-19 that are actually due to something else are the vast minority of the deaths caused by the virus, though he acknowledged it does infrequently happen.

“They’re going to review all of these eventually to determine for sure (why people died),” Wagner noted. “The numbers may go up and down once things slow down.”

Experts argue the more pressing problem is deaths were most likely undercounted due to a lack of testing – especially early in the pandemic.

The Journal of the American Medical Association, a peer-reviewed source, published a study from 12 doctors on July 1 that found from March to May alone in the U.S., there were an estimated 122,000 more deaths than normal for that time of year for all causes.

That was 28 percent higher than the number of reported COVID deaths at the time, and the authors concluded “official tallies of deaths due to COVID-19 underestimate the full increase in deaths associated with the pandemic in many states, ” reasoning at least some of the excess deaths were almost certainly due to the virus.

The authors wrote that they took that approach because it is a common practice to estimate the “mortality burden” of disease by examining excess deaths when there is a lack of comprehensive testing.

Claim: COVID has a mortality rate of around 2 percent, and the U.S. has one of the lowest mortality rates in the world.

Again, this is trickier than one might expect.

Mortality rates can be calculated in different ways, and the mortality rate changes depending on factors like age group, what mitigation measures are in place, location and more.

One common metric used is the Case Fatality Rate, which Our World in Data describes as showing how likely someone is to die from a disease if they contract it.

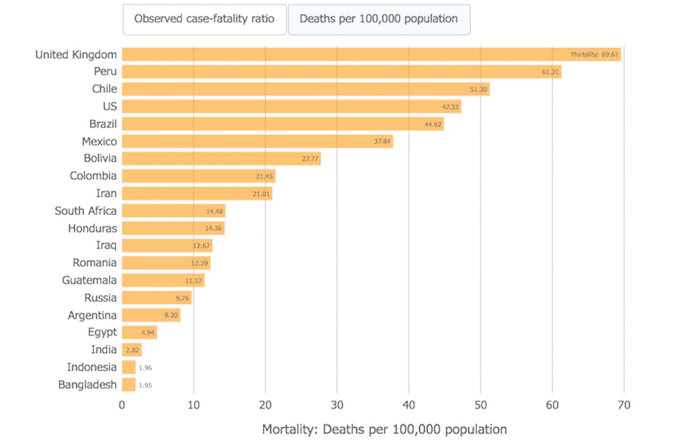

For COVID-19, John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center reports the Case Fatality Rate in the U.S. as of Aug. 2 was 3.3 percent, which was 13th highest among the 20 countries “most affected” by the coronavirus.

But Our World in Data cautions the Case Fatality Rate is always in flux, measures only confirmed cases and deaths, the full extent of which cannot be known in real time and differs based on demographics like age and location.

“That means that it is not the same as – and, in fast-moving situations like COVID-19, probably not even very close to – the true risk for an infected person,” Our World in Data explains, noting the Case Fatality Rate probably overestimates the risk of death due to how many asymptomatic people have the virus and underestimates it because more people are dying from the virus every day.

Another frequent statistic used to describe the mortality rate is deaths per 100,00 people.

This figure represents an area’s total population, including those with COVID-19 and those without it. Again, this comes with its own set of complications as it will similarly change and not capture the full scope of deaths in real time.

The advantage of this metric is that it provides deaths as a proportion of a population, not the most deaths overall.

For this metric, John Hopkins reports the U.S. had 47.33 deaths per 100,000 people on Aug. 2. On that same list of 20 countries, the U.S. had the fourth highest mortality, with Brazil, Mexico, Iraq, Iran and Russia among the countries with fewer deaths per 100,000 people.

The only countries with more deaths per 100,000 were the United Kingdom, Peru and Chile.

Either number, however imperfect, shows America’s mortality rate is both higher than 2 percent and not the among lowest in the world.