Back in time: Columbia cleaned up by beloved mayor

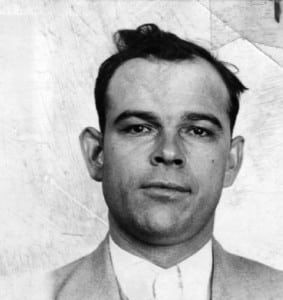

Buster Wortman

A.C. Metter

In this day and age of reality television, people may find it odd when they realize who has become famous. Ours is a culture that elevates what many would term “undesirables” to celebrity status. Times have certainly changed.

Or have they? One has only to mention gangsters of Illinois to begin the conversation. It is a subject that is fascinating to young and old alike, especially when exploring the deep connection between organized crime and Columbia’s colorful past.

Few have not heard of Al Capone when it comes to tales of Chicago gangsters. But down south, the likes of Charlie Birger, Buster Wortman, the Shelton Gang and Charles “Blackie” Harris are mentioned as the men who reigned as the most powerful of the Southern Illinois underworld.

During the years of Prohibition, most Southern Illinois coal fields were staffed by immigrants for whom the consumption of alcohol was a common and accepted way of life. To many of them, bootlegging became a natural choice once Prohibition was passed.

Birger, who had become a saloon keeper, saw Prohibition as a financial opportunity, and often fought with the Shelton gang over control of the coal fields in and around Harrisburg.

The battles for control of Birger’s territories continued into the mid-1920s, but the war finally ended in 1928, when Birger, arrested for ordering the murder of the mayor of West City, was hanged for his crime.

With Birger out of the picture, the power of the Shelton gang expanded and intensified. Gang members Wortman and Harris continued to work for the Sheltons, but their loyalty would soon be put to the test as the 1930s began.

In 1933, a Shelton-owned distillery being guarded by Wortman and another Shelton gang member was raided by federal agents. One of the agents was severely beaten, and the gang members were sentenced to Leavenworth prison.

While in Leavenworth, Wortman, feeling betrayed by the Sheltons, became affiliated with members of the Chicago mob who made his prison stay more comfortable. His alliance with the Chicago mob would prove helpful in the near future.

Upon his release from prison in 1941, Wortman found the world a much different place. With the end of Prohibition, the money to be made from bootlegging had fizzled out. The Sheltons, who had all but ignored Wortman after his release, now made much of their fortune from slot machines, pinball machines, horse parlors, craps games and card games.

However, after the Illinois government’s crackdown upon organized crime in the 1930s, the Sheltons had all but vacated much of their territory in and around the East St. Louis area. Much of their business was now done in the northern Illinois area including the town of Peoria.

For a while after his release, Wortman worked as a steamfitter in St. Louis. During this time, he surrounded himself with former members of the Shelton gang who shared his feelings of betrayal and by the mid-40s, Wortman’s new gang of gunmen had gained control of much of the area’s gambling racket, including former Shelton territory.

By the mid 1940s, slot machines had become fixtures in area establishments. Patrons at St. Clair and Monroe county taverns still enjoyed the usual card games in back rooms, but slot machines became a new form of amusement. In many cases, they became nuisances that caused strife in households.

In the late part of 1946, women in Columbia began complaining to then-mayor Albert C. Metter that the slot machines were causing major problems in their homes.

The men would go to the tavern and spend their paychecks on the slot machines. The women weren’t able to put food on the table with no money,” recalls Florence Metter Haberl, daughter of A.C. Metter.

Metter and city council members banned slot machines and gambling devices from the city limits in early January 1947. After that, establishments outside the city began to flourish as patrons continued to seek the amusement of the slots.

According to a 1947 article in the Columbia Star, “St. Louisans began arriving in droves.” Taverns and restaurants were purchased by these newcomers and the problem of the slot machines continued to worsen.

An old state law existed which allowed city officials to alleviate nuisances within a mile of the city limits.

“My father looked this law up and this helped get rid of some of the slot machines in places outside Columbia also,” Haberl remarked.

The news of Metter’s stance reached neighboring communities, and mayors of other towns began to follow suit.

But, as to be expected, those who gained profits from the “nuisances” were not happy with Metter and city officials. Wortman and his network of followers began to take action.

As the Columbia Star article reported, Metter received telephone threats in the fall of 1947, with the caller informing him that he should “Keep his damned mouth shut or else we’ll blow your house off the map and get you and your family.”

Haberl, who had recently married her high school sweetheart Cliff Haberl, recalls this incident as a time of stress for her father.

“The police surrounded my parents’ home for several days. Cliff kept a shotgun in our bedroom during that time,” she recalls.

Metter was called “spunky” in an article from the Millstadt Enterprise. He was quoted in several area newspapers, always standing strong on his views and never wavering from his original stance. As he concluded in an article from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “I am not interested in reforming this county, but I do want to keep this city and the immediate territory a respectable place to live in.”

In the end, the threats and problems promised by Wortman’s gang never materialized. Slot machines stayed out of Columbia and within a few miles of the city. Life returned to normal.

Albert Metter, already the mayor since 1933, went on to be elected to several terms as mayor, eventually retiring from political life in 1965. Citizens recall the gambling incident as a time when they rallied around their mayor and supported him, especially after news of the threatening phone calls was made public.

Although organized crime continued, the end of an era was close at hand. The Shelton gang died out after the 1947 and 1948 murders of Carl and Bernie Shelton. When their eldest brother Roy was also murdered in 1950, even though he had no gang affiliation, Earl Shelton packed the entire family up and moved to Florida. He lived to the ripe-old age of 96.

Wortman continued as a businessman and gangster in the area, but many noticed things becoming much quieter by the 1950s. He died in 1968.

Not long after his death, gambling became legalized in East St. Louis and the area experienced profits from gambling casinos.

Stories of these gangsters still mesmerize history buffs and many others, but for those people who remember those uncertain days of the 1940s, these tales are much more than legend and folklore.

“My father wanted what was best for this town. He stood behind what he believed. But I tell you, it was a scary time for us,” Haberl concluded.