A Baseball Life: Nelson Mathews

Now more than 50 years since he last played professional baseball, former major leaguer Nelson Mathews of Columbia looks back fondly on his career and the competitive drive that got him there.

There were plenty of peaks and valleys along the way for this “dead end kid” who grew up poor and on “the wrong side of the tracks,” as the 77-year-old phrased it during a recent sit-down interview inside his Columbia home.

“That’s what they called us,” Mathews said.

The Mathews family lived on the far southern end of Columbia Avenue that juts out just past Centerville Road, near a set of railroad tracks that used to run through town.

“We’d do plenty of hunting in the woods right behind the house,” he said.

Mathews remembers playing pick-up baseball and basketball games at Turner Hall from morning until night as a youngster.

“We didn’t have nothin’ else to do,” he said. “It was either baseball or basketball.”

When Mathews was 12, his father died from injuries sustained while working for the railroad in Dupo, leaving his mother in charge of raising the family.

“We never had any money,” Mathews said. “If that happened today, someone would get millions of dollars. He didn’t get anything.”

While certainly talented in baseball, Mathews initially dreamed of a hoops career.

“I dreamed about playing basketball,” Mathews said.

He played on the varsity squad as a Columbia High School freshman. During his junior year, the team went 23-3. As a 6-foot-4 senior, Mathews led Columbia to a 29-2 campaign.

He averaged 23 points per game as a senior and finished as the all-time leading scorer in school history, which stood until the Patton twins – Shawn and Ryan – surpassed his record in the late 1990s.

Mathews drew interest from the Chicago Cubs during his senior season on the diamond in 1959. The team’s vice president and a scout came to watch him play during a game in Freeburg.

CHS head coach Vern Smith told Mathews that Cubs officials wanted him to run the 60-yard dash for them after the game.

“I ran it in 6.8 seconds,” Mathews recalls. “I don’t know if that’s fast or not.”

Whatever the Cubs saw that day they must have liked, as team officials returned to Columbia on graduation night.

“My baseball coach said ‘Yeah, the Cubs are here again. They want to talk to you after you graduate.’ Because they couldn’t talk to you until after you graduated.”

In addition to receiving his diploma that night, Mathews signed a contract to play in the Cubs organization.

“They offered me $25,000,” Mathews recalls. “I said, ‘Where do I sign?’ I signed that check right away before they changed their minds.”

Two days later, Mathews was playing ball for $500 per month a few hours east in the Midwest League for the Paris Lakers.

“I had never been anywhere out of the area before that, you know,” he said.

His first minor league at-bats came against eventual major league pitcher Galen Cisco, who threw a no-hitter that day. Mathews had two hard-hit balls to the outfield off Cisco.

“I thought, ‘Wow, I hope it’s not this tough every game,’” Mathews said.

From Paris, it was over to the Morristown Cubs, a Tennessee team in the Applachian League. There, he befriended teammate Kenny Hubbs, who went on to win National League Rookie of the Year and a Gold Glove for the Cubs in 1962.

“We was like brothers,” Mathews said.

Hubbs decided to face his fear of flying by learning to fly an airplane. On Feb. 13, 1964, Hubbs died after crashing a small plane he piloted in Provo, Utah.

“I was really sad to hear the news,” Mathews said.

Mathews hit .368 at Morristown before breaking his ankle during a hard slide into second base.

“You can still see it’s crooked,” Mathews said while pulling up his pant leg. “They said I’d never play baseball again.”

But play he did.

In 1960, Mathews played for the Lancaster Red Roses in Pennsylvania and the Wenatchee Chiefs in Washington before gtting a late-season call-up from the big club.

On Sept. 9, 1960, Mathews was called on to pinch hit at Pittsburgh against star lefty Vinegar Bend Mizell.

“My legs were shaking and everything,” Mathews recalls. “He threw me a fastball right down the middle and I said, ‘Well shoot, I can hit that,’” Mathews said. “So, next one he threw it down the middle again and I hit a two-hopper over his head and into centerfield for a base hit.”

Mathews didn’t see much time in the majors in 1961 or 1962, spending most of his summers on minor league teams in San Antonio, Salt Lake City and Wenatchee. He led two minor leagues in triples in those years and was named an all-star.

Hitting behind Cubs greats Billy Williams and Ernie Banks – and ahead of Ron Santo – in the starting lineup, a 21-year-old Mathews smacked a first-inning grand slam off Dodgers pitcher Stan Williams on Sept. 16, 1962. He remains the youngest Cubs player to accomplish the feat.

In 1963, Mathews was up with the Cubs to start the season and was told he would get to play everyday in the outfield. He ended up only playing in 61 games.

“The coaches back then, they didn’t tell you anything. You had to figure it out yourself,” Mathews said.

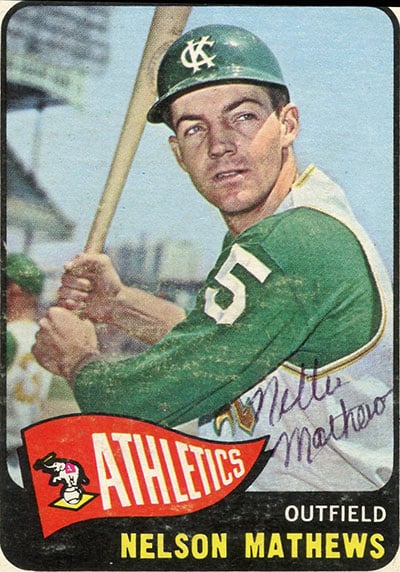

The Cubs traded Mathews to the Kansas City A’s for pitcher Fred Norman prior to the 1964 season. In Kansas City, he finally got to play everyday.

He played in 157 games that season, hitting .237 with 26 doubles, 14 home runs and 59 RBIs.

In 1965, Mathews started the season on fire for the A’s, going 20-for-50 at the plate. After that, however, an awful hitting slump relegated him to the bench with an average of .212 and only 67 games played on the year.

His final major league game was July 18, 1965 in Chicago, where he went 2-for-4 with a homer and two RBIs in the second game of a doubleheader against the White Sox.

“Then they just sent me to Triple A, those son-of-a-bucks,” Mathews said.

In 1966, the A’s traded Mathews to the Phillies but never made it back to the big show. Injuries forced him to hang up his cleats in 1967.

Still, Mathews played on the highest stage against some of the greatest to ever play the game: Stan Musial, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra and Roberto Clemente.

“It was fun,” Mathews said of his major league career.

Unfortunately, Mathews doesn’t receive a traditional pension because the rules for receiving Major League Baseball pensions changed in 1980. Mathews and hundreds of other ballplayers who played from 1947-79 do not get pensions because they didn’t accrue four years of service credit.

Instead, they all receive nonqualified retirement payments based on a complicated formula.

“I guess I was born 50 years too early for this game,” Mathews said.

In 1967, Mathews returned home to Columbia to enjoy life with wife Joan and their children Leslie, Kenny and TJ, working for Wonder Bread for 30 years before retiring in 1997.

He continued playing baseball, this time in the Mon-Clair League for Columbia. Mathews played 12 years in the league, winning a batting title in 1976.

“We’d play a doubleheader every Sunday and drink beer after,” he said. “We had a good time.”

Mathews passed down his baseball knowledge to his sons, coaching them until high school.

“The biggest thrill was when TJ played in the majors,” he said. “We went all over the country to watch him.”

TJ was drafted by the hometown St. Louis Cardinals and made his major league pitching debut in 1995.

While Nelson got to see his son play frequently, he was planning to attend every one of TJ’s game after retiring from Wonder Bread.

“I retired on July 27, 1997,” Nelson said. “On July 31, TJ got traded to Oakland for Mark McGwire.”

Nelson has dealt with various medical issues the past several years, including heart trouble and cancer on both his ear and cheek.

Still, he flashes a smile and is eager to sign his autograph for those who remember.

“I still get baseball cards in the mail from people all over asking for me to sign them,” he said.

Nelson offered this bit of advice to youngsters aiming for a career in professional sports:

“If you like to play it, give it all you got,” he said. “I’d do everything I could to get to the majors with what they make now.”

If you don’t already receive the Republic-Times newspaper, click here or call 939-3814 to subscribe.