Waterloo connection to historic East St. Louis Riot

Waterloo and East St. Louis may be separated by a 30-minute drive, but the history of these two communities is intertwined by a very crucial event in the aftermath of the 1917 East St. Louis Riot.

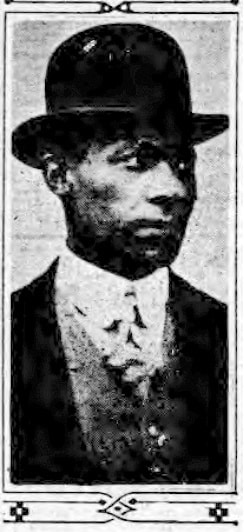

Dr. Leroy Bundy, an African-American dentist who made his home in East St. Louis, was found guilty of inciting the riot following a trial held at the Monroe County Courthouse in Waterloo.

Yet, Bundy was not even in East St. Louis at the time of the riot.

Andrew Theising, the author and co-author of books about East St. Louis history and an SIUE political science professor, provided insight as to how a man could be charged with involvement in a crime he was not even there for. But before that is told, the circumstances leading to the event need to be understood.

In the time leading up to the 1917 riot, many African-Americans were leaving southern states and settling in northern cities during the Great Migration. At the same time, white labor unions were gaining influence.

These historical conditions held true for East St. Louis.

“The labor unions at the Aluminum Ore (Company) plant walk out, they go on strike, and here are African-Americans who are coming in and they’re taking these jobs. They don’t realize they are being used to break a strike,” Theising said. “So, these white union folks are saying ‘Hey, you’re taking my job!’ and you can see the animosity that’s there.”

These conditions further fueled already existing tensions between the races in segregated East St. Louis, as Theising said Whites would often harass Black neighborhoods, sometimes even firing guns while driving through African-American neighborhoods. In response, Bundy spearheaded an armed neighborhood watch group. They decided to ring a church bell to signal when trouble was coming.

Bundy reportedly told the mayor weeks before July 1 that the watch group would start shooting if something was not done about the harassment. Yet, he was not in town in early July to witness the cumulation of it.

“On July 1 (1917), here’s this group of drunken teenagers, White kids, and they have their guns and they’re driving through the Black neighborhood at the south end and they’re firing shots, and so (someone) rings the church bell and the neighborhood watch is there and armed,” Theising said. “But, when the church bell rang, the police department heard it and they dispatched a police car to go check it out.”

By that time, the teenagers had driven away, and a police car arrived at the scene. Theising said he believes the neighborhood watch mistook the police car for the teenagers, and so they opened fire on the car.

Whether or not the neighborhood watch knew it was the police or not is a subject of debate. Some said the police showed their badge even though they were in an unmarked car, while others said even if this did happen, it could not be seen.

The next morning, as the bullet-hole-riddled car sits in the street, the White union workers gathered.

“The Whites basically say ‘The African Americans are going to attack us. We know they have guns, we’ve seen them out marching, we better put an end to this,’ so they met … in downtown East St. Louis, the union folks did, they gave inflammatory speeches and it was ‘go home and get your guns and come back here,’ and that’s just what they did,” Theising said. “It was about 10 or 11 in the morning, it was just before lunchtime, that this mob met and they started marching down Collinsville Avenue, and they started shooting. The first murder was of an African-American man right there at Collinsville and Broadway.”

Theising said the epicenter of the violence was between Collinsville and Fourth streets. In addition to murders, there was also looting and entire neighborhoods were burned. This continued until approximately midnight.

The official death count states nine White people and 39 Black people died in the massacre, but many say this is a severe under count.

According to smithsonianmag.com, many say over 100 African-Americans were murdered. Even with the official death toll, June 2, 1917 marked the bloodiest massacre in U.S. history until the 1991-92 Los Angeles Riots.

After Bundy returned, he was accused of planning the riot, with his comment to the mayor being seen as evidence. His attorneys asked for a change of venue, as they said Bundy could not get a fair trial in Belleville. So the trial was set in Waterloo.

Bundy was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.

“The court case was quite … fraudulent,” Theising said. “There were people who just outright lied on the stand, and it was sort of like, ‘We’re going to believe this person but we’re not going to believe that person,’ and ‘This person can testify, but not that person.’ Even though he was found guilty, his appeal went all the way up to the Illinois Supreme Court and the Supreme Court overturned his conviction. They were embarrassed by the way the trial was conducted and they said it was a miscarriage of justice and he was set free.”

After being set free, Bundy returned to his hometown of Cleveland, where he then served on the city council.

For more information on East St. Louis history, check out Theising’s books. They can be purchased at arcadiapublishing.com.