Remembering Columbia’s fearless pilot

One century ago, a feat that was considered impossible at the time, or at least too dangerous to attempt, was completed as two members of the Army Air Service successfully flew over and into the Grand Canyon in an effort to provide an aerial survey.

While neither man served overseas during World War I, their bravery and skill in accomplishing the historic feat lead to further advances in aviation technology based on the findings from the treacherous voyage.

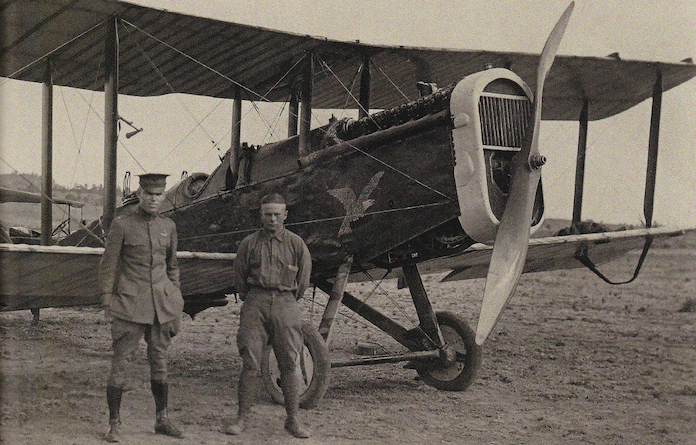

One of the men involved in the feat was Sergeant Arthur Juengling of Columbia. He joined the Army Air Service in 1918 and specialized in aviation research for a technology that was in its infancy, with the Wright Brothers’ famous flight occurring only 15 years prior to Juengling’s enlistment. He was co-pilot for the flight into the Grand Canyon that commenced June 10, 1921.

The pilot was Lieutenant Alexander Pearson. He joined the Army Air Service and remained stateside as a flight instructor in several locations, including Scott Field in Belleville.

While several pilots flew close to the rim of the canyon, its size and topography created previously unexplored climate phenomena that put the success of the flight in serious jeopardy.

An article about the flight from a June 17, 1921, issue of The Williams News, a nearby Arizona paper, said the flight “had been declared by experienced airmen as one of the most hazardous that might be undertaken.”

A failed try at the task had been attempted the prior year. Seeing it as a mark of shame to have not accomplished its goal, the Air Service chose Pearson for the second attempt. Pearson had made a name for himself as a daring airman who had already set several air speed records and had attempted a “transcontinental” flight from Florida to California in February 1921 before engine troubles grounded the flight in the middle of Texas.

Nevertheless, Pearson was selected as the pilot to traverse the Grand Canyon. Juengling was assigned to be his co-pilot and aided in recording data and photographing the canyon from the air. Their mission was conducted as a way to discover the best aerial routes for “airline passenger and mail service through the canyon.”

The duo had worked together before on reconnaissance missions along the U.S.-Mexico border. They set out to plan their pioneering flight into the canyon on May 31. On June 10, they flew for two hours and 40 minutes in and around the Grand Canyon, experiencing heat swells and turbulence created by the temperature difference from the varying depths of the canyon.

The feat was witnessed by hundreds of onlookers “speculating as to what part of the vast chasm below would receive the wreck of the daredevils’ plane.”

Pearson said later that he wouldn’t describe the flight as “exactly a pleasant pastime in windy or irregular weather.”

While Juengling’s part in the historic flight was covered locally in the Columbia Star, the national media focused on Pearson’s role, as he was the pilot and had already garnered fame from his previous aerial accomplishments.

Pearson did not diminish Juengling’s vital contribution to the success of the flight, though. Referring to Juengling as his “mechanicician,” Pearson noted he “could not get along without” the help of his co-pilot.

After the flight, both men continued in the Air Service, and both died in airplane accidents. Juengling died near Fort Bliss, Texas, in June 1922 and Pearson wrecked in September 1924 while preparing for his second Pulitzer Race at Wilbur Wright Field.

Just before his death, Juengling wrote to his parents that he planned to move home when his enlistment ended in July 1922 but he and another man were killed when the plane they were flying crashed into a mountainside on June 2.

As reported in the Waterloo Republican, the “funeral cortege was by far the largest ever seen” in Columbia, with some estimates claiming 10,000 people in attendance.

The Republican said the June 11 funeral was “impressive and fitting for an American soldier. The Waterloo Times also described a procession that had 400 vehicles “besides the thousands who made the trip on foot.”

“The remains were borne to their final resting place on a caisson sent out by Battery A. of St. Louis, which was drawn by six beautiful black horses under,” and “was headed by the recruited remnant of the old 138th Regiment Band and the local legion boys were next in line,” among other military groups in the procession.

Juengling was buried in the cemetery of Immaculate Conception Catholic Church in Columbia.

“Mayor Rapp delivered an impressive funeral oration and songs were sung by the Y.P.L. Quartet of Waterloo and the singing society of the Catholic church,” the Times article continued.

Ironically, the “aeroplanes which were supposed to drop flowers on the grave were out of commission and failed to come.”

Juengling might have passed into history as a side note in Pearson’s story had it not been for his nephew, Stephen Schmidt, who grew up in the same house as his uncle on Main Street in Columbia.

As a child, Schmidt remembered being “fascinated” by a family album containing memorabilia of his late uncle’s life, including newspaper articles and pictures about the Grand Canyon trip as well as other pictures of plane accidents Juengling was present during while he was an aviation researcher.

He shared his findings with the Republic-Times to celebrate the event’s 100th anniversary as well as Arizona Highways magazine, who did a story about the flight in January 2020.

Schmidt speculated that the funeral was such an event not only because of the Grand Canyon flight but also because many World War I servicemen who died during the war were either buried in Europe, never recovered, or were returned home years after their deaths.

The Waterloo Republican reported about Harry H. Keane, who was buried in Ss. Peter & Paul Catholic Cemetery on June 27, 1921. He died in France on Sept. 15, 1918.

Juengling’s connection to the community before his enlistment also contributed to the size of the funeral.

Juengling worked at the Weinel Lumber Company and hardware store in Columbia as a teen. Schmidt recalled seeing model airplanes the young Arthur Juengling had built still being displayed in the store’s windows in the mid-1950s.

Schmidt also remembered his family having the old “Brownie” camera Juengling used during the canyon flight, among others.

Schmidt said he would probably never be able to track down the model cars and camera, as well as his uncle’s violin, if he tried. Fortunately, he has made it possible for others to discover his uncle’s story – one of many innumerable tales from our country’s servicemen.