Farmers feeling coronavirus effects

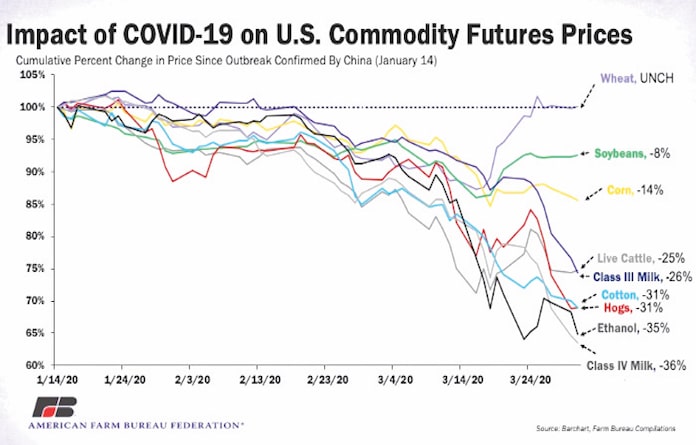

prices through March.

Like any other business, the ripple effects of the coronavirus pandemic have affected the farming industry nationwide, including in Monroe County.

According to the most recent data from the American Farm Bureau Federation, dairy prices plummeted 26-36 percent in March, corn futures dropped 15 percent, soybean futures went down 8 percent, ethanol prices fell 35 percent and hog futures declined by 31 percent.

“(Farmers) are facing make-or-break struggles like many Americans,” said Zippy Duvall, the federation’s president. “After years of down farm economy and damaging severe weather, the COVID-19 ripple effects are forcing farmers and ranchers to face heartbreaking financial realities.”

In Monroe County, the severity of the pandemic’s impact varies from farmer to farmer and type of commodity, with livestock and dairy farmers seeming to be hit the hardest.

Bruce Brinkman, a swine farmer near Valmeyer, said that while he has moved all his pigs, he knows a farmer who has roughly 1,000 head of hogs that he must get rid of by June 15.

But he does not know where those animals will go.

“What he does there, I don’t know,” Brinkman said. “I’m working with him on trying to get some things put together, but that’s going to be a challenge.”

Brinkman (left) at his pig farm last year

with state Rep. Nathan Reitz (D-Steeleville).

Part of the problem is the sharp drop in prices.

“The price of the commodities we’re selling has gone to nothing,” said Mike Henry, a dairy farmer in Red Bud who is a member of the Monroe County Farm Bureau. “If the futures market holds true, we’ll be done by the first of the year.”

This pandemic came at a particularly painful time for dairy farmers, Henry said, because the market was projected to take some steps forward after five years of stagnation or decreases.

“We were predicting to get $20 milk for 2020, and the futures market is now at $12,” Henry said.

The situation does not seem as bad for now for those who farm crops because those can be stored long-term, unlike livestock or dairy. That is a move many farmers are making.

“Our grain prices have eroded quite a bit,” Dale Haudrich, who farms corn, beans and wheat near Hecker, said. “We lost a lot of market price. The price now is well below the cost of production, so something’s going to have to happen or we’re not going to survive this.”

The problem farmers are facing is a multifaceted one, with the main issues being the systems used to get their products to consumers and consumer demand.

In the former case, Brinkman explained that about 60 percent of meat typically goes to places like restaurants. Henry said businesses and schools are also big milk buyers.

With those places closed, however, the delivery system cannot rapidly change to get more products to places like grocery stores, which also do not readily have the capacity to take larger shipments.

“We have product out here that we want to get to the consumer, and we have plenty of it,” Brinkman explained. “It’s not that the system is broke. It’s just that the system isn’t tooled in this direction.”

Additionally, Brinkman said there have been problems at meat packing facilities nationwide due to COVID-19 outbreaks. President Donald Trump recently ordered those plants to reopen with safety measures in place, but they will not be operating at full capacity.

Even local processors, who Brinkman said farmers might turn to in an effort to at least give some meat away to food pantries so it does not go to waste, cannot help because they are at capacity.

Henry echoed Brinkman’s explanation of the problems and said there have also been unforeseen problems in the dairy world, like the plant he normally takes his milk to running out of plastic to make jugs.

Haudrich said demand is more of the issue for grain farmers, as about 40 percent of corn in Illinois goes to ethanol plants.

He said there are 13 of those facilities in the state that typically produce 1.8 billion gallons of ethanol each year, but two of those plants are currently closed and the others are producing at 50-70 percent capacity since people are driving less.

Moreover, the demand for grain to feed livestock has decreased as farmers are being cautious.

“It’s a big rippling effect to the ag economy,” Haudrich summarized.

With all these challenges, Brinkman said swine farmers who cannot move their animals are in a terrible position because their next shipment of hogs is already on the way.

“You can’t just stop production overnight when you have livestock,” Brinkman said. “So that’s a heart-wrenching decision on what’s going to be done.”

Henry said the latest information showed that dairy framers throughout the country were disposing of an average of 11,000 loads of milk a day because they could not sell it. Each load is about 5,000 gallons.

While that is getting better, Henry said the product is not being sold at a profit, which means farmers may have to resort to slaughtering some of their cows for meat because it is not feasible to continue feeding them without a return on investment.

“They’re just throwing milk away,” Henry said. “We can’t do anything different. Our system is set up and the cows are set up to eat and produce this much milk every day. If it goes on like this and the price goes on like this, you’re going to get rid of the cows and produce less milk.”

Even grain farmers may be forced to make similarly fraught choices if prices do not improve by the time bills are due or next year’s crop needs to be stored.

“We’re hoping it rebounds before they have to pay bills and sell it and before next fall’s harvest,” Haudrich said.

Seeing this, the government is aiding farmers like other industries.

The Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security Act provided $9.5 billion for farmers and ranchers. Additionally, the government announced a $19 billion coronavirus assistant program on April 20, with $9.6 billion slated for livestock farmers.

Farmers through that program will get a single payment based on price losses that occurred between January and April 15, with producers being compensated for up to 85 percent of loss during that period.

The second part of the payment will be for losses from April 15 through the next two quarters and will cover 30 percent of those expected losses.

Those payments are capped at $125,000 per commodity with an overall limit of $250,000 per individual or entity.

“I think the livestock people are taking a beating,” Brinkman said, noting farmers are losing as much as $50-$100 a head. “Any stimulus we can get for the livestock folk is something we should be supporting 100 percent. They’re taking it on the chin.”

“We’re a small business just like many others,” Haudrich added. “So if there’s an offer (for aid) out there, I think we ought to take it seriously and look at it individually.”

But Brinkman also said he thinks the processors might need help more than farmers. And Henry said the aid will help, but it is not a silver bullet when it costs a farmer like him $450,000 per month to run his operation.

“It’s a big number when you tell the public in the newspaper,” Henry said of the aid. “They think we’re just making bank.”

With all the uncertainty surrounding agriculture, farmers are in a similar place as almost everyone else.

“It’s going to be scary time ahead,” Haudrich said, noting other countries who are further along in the pandemic have not seen their demand return. “We don’t know where it’s going to go.”

“I think we’re still going to have challenges a year from now,” Brinkman agreed.