Nurses try hard to keep up the fight

Whether manning a hall in a long-term care facility or an intensive care unit in the largest hospital in St. Louis, local nurses in every sector of health care are facing the multiple tolls of the present COVID surge.

Last week, St. Louis area hospitals continued to exceed record numbers of COVID patients.

As emergency room waits at Mercy Hospital South in St. Louis County surpassed 20 hours last week, things aren’t looking good for the most critical of patient care either, as a nurse in Barnes-Jewish Hospital’s Neuro-ICU testified.

“We are the premier hospital in the Midwest … and I had an open bed one night (two weeks ago),” the RN, who wished only to be identified as Alex, said. “I work in the Neuro-ICU, and we have a surgical ICU, we have a medicine ICU and then we have a trauma ICU. Every single one of those were full. I had the only open ICU bed at Barnes-Jewish Hospital.”

The patient transferred to the open bed was not even one with a neurological health concern, Alex noted.

At the same time, the Neuro-ICU is “absolutely full” of patients who are suffering from strokes caused by clotting in a blood vessel that prevents their brain from receiving the blood supply it needs, Alex said. This type of stroke is considered one of the many complications associated with COVID-19.

Studies show up to 4.9 percent of COVID patients experience an acute ischemic stroke during their first hospitalization, Texas’s St. Luke’s Health website states.

Alex said even with this, there is a common misconception that the current surge is not as harmful as previous ones.

“COVID is always downplayed. ‘Oh it’s getting better. The death numbers are lower,’” he said. “That’s fantastic the death numbers are going down, but it’s only because the research that we’re doing with COVID is progressing … it’s just because we have a far better understanding of it.”

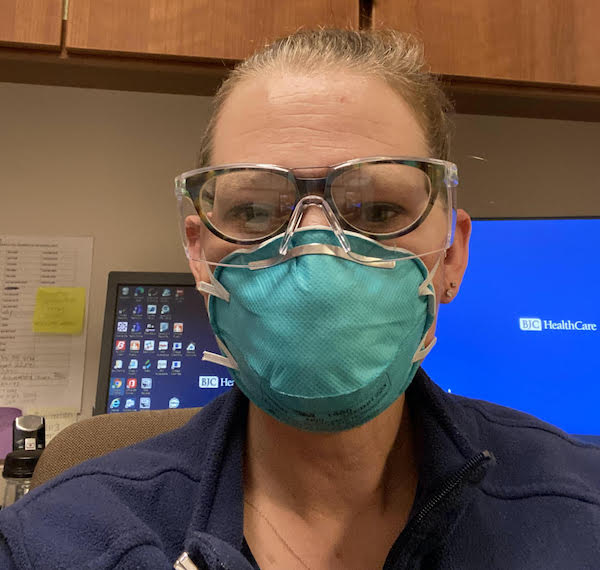

BJC HealthCare canceled all elective procedures throughout its hospital network effective Jan. 6. This meant that Deanna Wreath, a gastroenterology nurse at Memorial Hospital Belleville and Shiloh, is once again seeing her work shift dramatically during the pandemic.

“This is the second time that we’ve been affected by a surge to where we completely shut down cases except for emergencies,” Wreath said. “We will be covering the BJC testing site facility in Swansea and we’ll be helping out other areas of the hospital for the next 2-4 weeks.”

Wreath first saw her GI unit be shut down from May to June 2020, during which time she volunteered in the ICU. If she has time to spare after working at the testing site, she will ask to help in the ICU again.

Unlike when Wreath’s unit temporarily shut down in 2020, the highly infectious Omicron variant is causing an already small workforce to be stretched even thinner.

BJC Chief Clinical Officer Dr. Clay Dunagan explained in a Jan. 5 press briefing by the St. Louis Metropolitan Pandemic Task Force that there are a “substantial” number of health care workers absent from work due to being infected with the virus, and this ultimately lowers patient capacity for hospitals.

As of Monday, Oak Hill Interim Administrator Kim Keckritz said 12 staffers were absent at the senior living facility in Waterloo due to the virus. She said the CDC’s newly revised quarantine guidance – which states one can go back to work on day six provided they do not have symptoms – is keeping this number down.

Wreath said Memorial Regional Health Services is seeing staff out with COVID-19 as well.

“Last time, even before vaccinations, I think only a couple of the staff members were out,” Wreath said. “This time, it seems like it’s affecting us vaccinated (hospital staff) more. I just got over it myself.”

Alex explained Omicron is infecting health care workers frequently as it has a higher viral load, meaning it is heavily transmissible. Coupled with the fact health care workers are in extremely close proximity to patients, their likelihood of getting sick is larger.

“Say that you’re a nurse, doctor, speech pathologist or what not, and you’re leaning over this patient and you’re literally inches away from them and they cough in your face … you’re getting a whole lot more of that virus at once than just having a conversation (feet away),” he said. “Yes, communicable spread is terrible and it does have a lot of mortality, but the worst spread type is caregivers.”

While the vaccine does not necessarily prevent one from becoming ill with COVID, and the Omicron variant seems to be behind more breakthrough cases, being vaccinated – and boosted – can prevent serious illness.

As the St. Louis-Post Dispatch reported, Dunagan said a recent survey found just 1 percent of COVID patients within BJC HealthCare hospitals had been boosted.

Even knowing the chances of being seriously ill with COVID is slim for vaccinated health care workers, the potential of getting sick still sparks anxiety, as Oak Hill Licensed Practical Nurse Jennifer Grider explained.

“Everybody – the staff, the residents, housekeeping, dietary – is on heightened anxiety. You feel like a sitting duck and it’s very stressful,” she said. “You do everything possible that you can (to prevent it) … and people are still getting it. You wash your hands, you sanitize, you do everything that you’re taught.”

In addition to staffing shortages, health care often finds itself grappling with limited resources. Alex said supply chain issues have recently been affecting operations in the Neuro-ICU. What supplies may be missing varies from week to week.

While it may seem like more of an inconvenience, the consequences can be drastic, Alex said.

“Every single step you add to us having to do in our job literally takes away 20 seconds we can be with our patient,” Alex said, adding this is enough time for a patient to go into cardiac arrest or suffer another health crisis.

While Keckritz said Oak Hill is not necessarily hurting for medical supplies, it is facing challenges of its own.

Grider said Oak Hill has been navigating seemingly ever-changing guidance from the Centers of Disease Control, Illinois Department of Public Health and other entities on congregate care visitations.

“What’s so frustrating to me – and I understand they’re trying to do the best they can with everything – is how everything changes. It’s like you think you’ve got it in your brain and you’re going to explain it to the family and then it changes again and then it makes you feel like a doofus,” Grider said.

In addition, when visitors are allowed in any capacity, it adds another dimension to Oak Hill staff’s job: they must ensure all visitors are following the proper precautions, such as masking and visiting limitations.

When visitors are not allowed, it creates an even larger struggle.

“I’ve literally seen them when we’ve had to quarantine and they’ve had to stay in their rooms, get very depressed and stop eating,” Grider said. “Some of them lost the will to live. We’ve tried antidepressants and multiple things with window visits.”

Keckritz said these mental impacts are why the CDC revised its congregate care visiting rules to allow visitors in some capacity unless there is a very severe spread among residents and the local health department and Oak Hill feel allowing visitors would contribute to the spread.

She said this is not the case right now – visitors ages 16 and above are allowed provided they do not show signs of COVID-19 – and doubts it will be.

Residents and patients are not the only ones being mentally taxed by the pandemic. For nurses, what they see haunts them.

Alex and Wreath have both witnessed individuals dying of COVID who are younger, otherwise healthy individuals.

Recently, Alex had a comfort care patient, meaning there was nothing health care professionals could do to “cure” her or otherwise prolong her life, die.

The woman was in her early 40s and died alone due to COVID complications. As the unit was so short-staffed, a nurse was not available to be in the room with her. Making it even worse, Alex said, was knowing her death may have been prevented if she had taken precautions.

The vast majority of COVID deaths in Monroe County since vaccines became available involved unvaccinated individuals, Monroe County Health Department Administrator John Wagner told the Republic-Times.

“People who shouldn’t be getting as sick as they are with it are,” Wreath explained, stating she has seen individuals who do not have any underlying conditions dying, just as she did in 2020 while working in the ICU. “Like a 45-year-old healthy man, we just saw expire in the unit on Dec. 23. It’s still happening, unfortunately. I’m not sure if he had the new variant. I don’t know the particulars, but unfortunately, it doesn’t seem like we have a handle on this.”

This, and having just recovered from the disease herself, prompted Wreath to issue a strong message: mask up, vax up and avoid large gatherings.

“Don’t gamble with your health. Protect yourself,” Wreath said. “I also would like to remind them that even myself, I got lazy. If I ran somewhere, sometimes I wouldn’t wear an N95 or I would just slip a regular mask on, or maybe not even that, I’m going to be honest … but don’t gamble with your life. My whole family, we were lucky and we were very sick. We had very bad body aches and trouble breathing. I’ve never felt that achy in my life.”

On top of fear of getting sick, many nurses are experiencing burnout, a state of exhaustion characterized by stress and anxiety that makes it hard for one to do their job.

“I think it kind of feels like when you’re getting ready to go to work and you just sit in your car and you’d rather just cry your eyes out than go to work and do what you need to do,” Wreath explained, noting that while she has not hit this point, she knows of nurses – both new and retiring – who are debating leaving the field.

As detailed in U.S. News and World Report, Dr. Victor Dzau, president of the National Academy of Medicine, found 60-75 percent of clinicians experienced exhaustion, depression, sleep disorders and/or even post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I cannot tell you how many times I’ve come home where I’m just broken, because I’ve had days where … I’ve had multiple people die on me in one night,” Alex said. “That night that that happened, I thought ‘There’s no other career … where you see so much death at once.’”

Yet, there’s something that keeps each nurse going.

“Every day is a challenge, but then you have a family member that says, ‘I know mom’s going to be taken care of because you’re there,’ or a resident that says, ‘I feel safe when you’re there.’ Sometimes that makes your day,” Grider said.

For Alex, it’s seeing the impact of organ donations.

“You’re just standing there on the side of the hall with someone that decided to donate themselves, and then you hear and see the reactions from the recipients,” he said. “There is hell in being a nurse, but there is something that you can’t get without being a nurse.”

As strange as it may sound, there is actually one thing from the beginning of the pandemic that can be brought back to help health care workers, Wreath said.

“I think that the whole (health care) hero thing was really nice when it first started and there were a lot of people thanking health care workers and everything, but it sure didn’t last very long, even through the pandemic,” Wreath said. “I just want to remind people how hard the job has become. Even just a ‘thank you’ or an ‘attaboy’ goes a long way with people.”